On October 15th, the Packard Foundation announced that it had “achieved the goal of operating its headquarters building at net zero energy by generating more than enough electricity to meet is needs during the first full year of occupancy.” It is the largest building to-date to receive Net Zero Energy Building Certification through the International Living Future Institute. The architecture firm EHDD created, for The David and Lucile Packard Foundation, a thoughtfully designed building that approaches sustainability from an integrated perspective of landscaping, water and energy conservation, material resource conservation, and building occupants’ patterns. A careful orchestration of various design strategies addressing those matters and meticulous operations and maintenance practices has resulted in NZE Building and LEED Platinum certifications for the building.

Landscaping and Water Conservation

The site of the project used to be covered with unoccupied buildings and asphalt parking lots with 97% imperviousness. The new building’s footprint results in 35% imperviousness. EHDD and its landscape architects, Joni L. Janecki & Associates, transformed the site into a Californian landscape consisting of grassland and woodland ecosystems made up of mostly California-native plants sourced within 500-miles of the site. Native planting not only reduces the need for watering and chemicals, but also provides familiar food and shelter for the birds and insects.

At the entry court a 25-year old Live Oak tree, grown from an acorn on a property near Clear Lake, anchors the entrance of the property. Landscaping also extends to a green roof covered with California coastal succulents outside the Board Meeting Room, and rain gardens along the length of the sidewalk fronting both sides of Second Street. The plantings in the landscapes, green roof, and rain gardens all help to slow down the amount of rainwater volume that flows into the storm drain system.

Water Conservation

While landscape design strategies were used to minimize the use of irrigation water, resource-saving design strategies such as using low-flow plumbing fixtures were also implemented to reduce the overall usage of potable water. The Packard Foundation installed Los Altos’ first rainwater harvesting system for indoor use and it is projected to achieve a 69% reduction in the use of potable water.

Rainwater from the roof is collected through gutters and downspouts and routed to a 20,000-gallon underground cistern. The collected water is then filtered and re-used, and is projected to meet 90% of the toilet flushing needs and 60% of the irrigation demand. If the cistern overflows, the water gets fed into a detention pond designed to minimize stormwater before it enters the public storm drain system. The building maintenance crew works on refining and overseeing the rainwater harvesting monitoring system.

Energy Conservation

The results from the greenhouse gas assessment and energy usage modeling served as a starting point for figuring out how to minimize the use of energy with various design strategies. In their approach to achieving net zero energy usage, EHDD and its MEP and energy modeling engineer, Integral Group, started off with a 65% energy use reduction target driven by design strategies addressing the building envelope design, HVAC systems, and daylighting. The other component key to minimizing energy use was reducing the building’s plug loads. The design team’s analysis of existing equipment loads concluded that plug loads took up 60% of the energy usage model. Thus, the Packard Foundation revamped its purchasing plan to target acquiring the top-5% of Energy Star equipment.

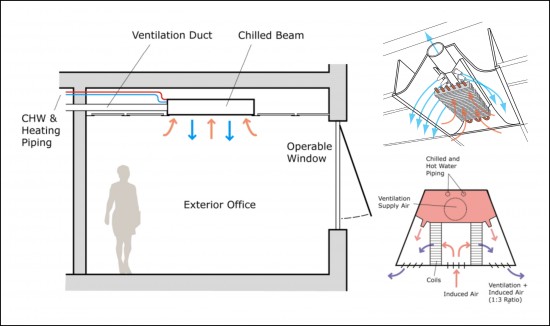

A combination of triple-element windows detailed to eliminate thermal bridging and continuously insulated R-24 wood-framed walls essentially eliminated the need for perimeter heating at most locations. This reduced the size of the mechanical heating system, and the low heating demand eliminated the need for gas and allowed for electrical heating provided through the ventilation supply air. High-efficient chilled beams and radiant panels provide cooling using chilled water created at night by compressor-free cooling towers and stored in a 50,000 gallon underground tank. A solar thermal system, supplemented by a backup system, is used to provide hot water. To offset yearly energy demand of the building and site, a 285 kW solar photovoltaic system was installed. Environmental gauge monitors are installed at every connector hall and computer desktop so that occupants are informed of how the building is performing. The environmental gauge indicates wind direction, wind speed, outside temperature, outside relative humidity, and the building’s energy usage; and advises on whether or not it’s appropriate for occupants to open the windows.

Material Resource Conservation

The architects’ approach to material selections considered different ways to reduce the emissions from the embodied carbon of selected building materials and the need for virgin material. Structural engineer Tipping Mar worked closely with them to design structural systems that became a part of the architectural features and would minimize potential repairs after major earthquakes. The wood and steel hybrid structure consisted of advanced wall framing techniques such as framing at 24-inch on center to save on wood, reduce thermal bridging, and increase the area available for wall insulation. All wood members were FSC-certified except for the doors, which were created from Eucalyptus wood salvaged from the Doyle Drive construction project at the San Francisco Presidio. Any concrete used on site included a 70% slag replacement of Portland cement. The Mt. Moriah stone tile cladding came from the border of Utah and Nevada within a 500-mile radius, while the exterior copper cladding with an integral finish was made from 75% recycled copper. By the end of the project, 95% of the materials from deconstruction and construction were diverted from the landfill and recycled.

Transportation Emission Reduction

The Packard Foundation and EHDD’s survey of how staff members commuted to work concluded that only 67 parking spaces were needed for the 121 staff members. This gave them a strong case to make against the City’s requirement of 160 parking spaces and resulted in the elimination of an $8 million underground parking garage from the project budget. Showers, bicycle lockers, electric car chargers, and VTA light rail/CalTrain/bus passes are provided to encourage staff to use of alternative transportation modes. All large meeting rooms are provided with web conferencing systems so that air travel could be reduced yet people can still meet face to face.

Some of the deep-green design strategies listed above are fairly straightforward and some of them are a little more complex. Some are applicable to all types of projects and some are not. The key is to understand the long-term implications of the various strategies, select the appropriate ones, and find a way to balance them without negating their benefits. With the long-term goal of achieving sustainability throughout the organization, The David and Lucile Packard Foundation has found a way to exemplify the integrated design process in the creation of its green and sustainable headquarters and set high standards for others to follow.

Be the first to comment