Earlier this year, I had the opportunity to take a private tour of The David and Lucile Packard Foundation’s newly built headquarters. It’s an elegant, well designed, and very green office building located in downtown Los Altos, California. It has an understated presence that respects its surrounding neighborhood and provides a strong anchor for the street fronts. Architects Scott Shell and Brad Jacobson of EHDD and CFO Craig Neyman of the Packard Foundation were on-hand to talk about this building that so smartly represents the Foundation’s core values and commitment to conserving the earth’s natural resources.

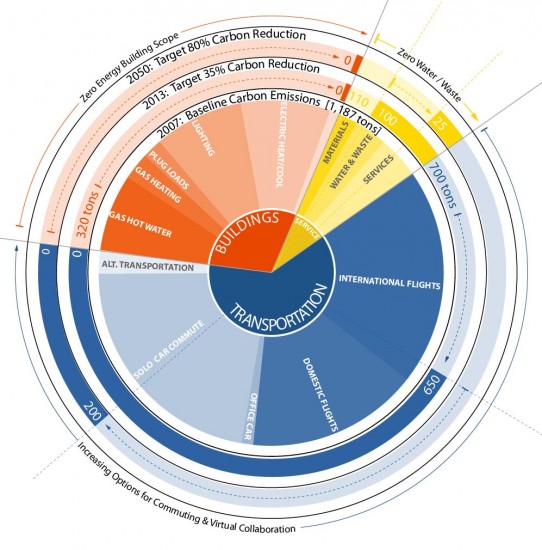

When the Packard Foundation first approached EHDD in 2007, they wanted EHDD’s recommendations on the type of building that they should build. EHDD’s response, to take an overall organizational approach to sustainability and to create a net zero energy (NZE) building, turned out to be inline with the Packard Foundation’s values. EHDD and the Packard Foundation also decided to base their sustainability goals on California’s Global Warming Solutions Act of 2006, which mandates statewide carbon reduction of 80% by 2050.

Unlike most projects, the Packard Foundation’s project started off with a greenhouse gas (GHG) emission assessment. This included assessing purchasing and internal operations strategies, air travel frequency, and employee commute patterns. The assessment also calculated the emissions created by hot water loads and energy loads (heating, cooling, ventilation, lighting, and plug loads). The findings served as a starting point in determining how general and specific design strategies could help reduce the organization’s various GHG emissions and at the same time help achieve its sustainability goals.

The creation of the LEED Platinum, two-story building allows the Packard Foundation to bring together staff members who were originally spread out at multiple locations and to enhance staff collaboration through the building’s design. The building consists of two 40-feet wide office wings, connected by two enclosed bridge corridors, that wrap around a central courtyard accented with native Californian plants and seating areas. The courtyard often serves as an impromptu meeting spot.

It was important to the Packard Foundation that the building fit in with the existing urban grid layout. As a result, the building is oriented 40 degrees off of true north, which is not ideal for solar orientation. EHDD made sure that glare was controllable and direct sunlight was kept out of the southwest-facing spaces. A layering of roof overhangs, balconies, trees, interior blinds, and automated exterior blinds on all the southwest-facing windows provides both a practical solution to solving sun and glare issues and a multi-faceted facade design. The exterior cladding is a palette of warm hues reminiscent of California’s landscapes–wood, copper, and stone tiles–accented with metal and glass.

The transparency of the building is most pronounced at the facades facing the central courtyard and provides a pleasant indoor/outdoor quality for its occupants. On the ground floor located at both the main meeting room and main hall, large sliding glass doors open up to the central courtyard to bring the indoors out and the outdoors in. Flexibility of the spaces can also be seen in the layout of office neighborhoods and their versatility in re-configuration. Interspersed between the neighborhoods are transparent connectors that serve as lounges for seating and informal meetings.

The building’s narrow footprint provides all occupants direct access to daylight, views, and operable windows from their workspace. It also allows for 81% of the spaces to have enough daylight so that lights automatically dim when there is sufficient daylight level. The ground floor height was set so that it maximized the reach of daylight into the spaces. Combined with other design strategies such as LED task lights equipped with occupancy sensors at each desk and upper floor skylights and light-shelves, these design strategies helped achieve a 40% reduction in energy usage attributed to lighting.

In its commitment to building a green and sustainable building, the Packard Foundation also committed to ensuring the proper functioning and maintenance of the completed building. Calibrating the building was a critical task. During the first year of occupancy, the architects, engineers, and commissioning agents teamed up to provide qualitative training, evaluation, and rigorous monitoring and commissioning of the building systems. They worked closely with the facility manager to resolve performance problems and document any changes to the systems.

The David and Lucile Packard Foundation’s headquarters serves as an inspiration that exemplifies how green building methods, materials, and technologies can help us achieve reduced carbon emissions. The project is awaiting Net Zero Energy Building certification from the International Living Future Institute.

In a follow-up article, I will be focusing on the different design strategies that address landscaping; conservation of water, energy, and material resources; and transportation issues.

Be the first to comment